Introduction

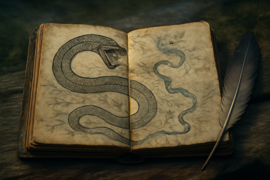

Long before highways carved clean paths along the Tennessee and Alabama rivers, the water carried whispered tales of serpents as long as a hollowed log and as silent as the moss clinging to cypress roots. Even now, when moonlight glimmers on the current and fireflies stitch golden threads in the bayou air, locals hush their voices against the hush that follows—a silence bearing witness to something vast, unseen, and ancient. In cabin porches sprinkled with gravel, fishermen spin stories of hooks snapped overnight, shadows gliding beneath rafts, a rolling surge that unsettles skiff bulbs at zero hour. They speak of distant banshee cries across the stillness, voices not born of any human throat but echoing through mist like the laughter of the drowned.

Over generations, families have tabulated tragedies on ledger pages hidden beneath floorboards: a child missing at the bend where walnut trees lean in, a pirogue crushed by an unseen weight, cattle swept away in a single convulsion of waves. Scholars have measured pH levels, divers scanned silted channels, and still the legend persists—tales so potent the riverbank grasses lean as if to hear better. Those brave enough to paddle out at twilight insist on lifejackets, whispered prayer, and salted charms passed down by creole grandmothers. Whether myth or manifestation, the serpents of Tennessee and Alabama rivers have braided themselves into the cultural undercurrent of this landscape, binding past losses to present fears, and drawing the curious into their silent, swaying world.

1. Origins of the River Serpent Myth

The earliest recorded mention of colossal serpents along the Tennessee and Alabama waterways dates to 1798, when French trappers noted unidentifiable crashings in submerged hardwood forests. They sketched vague outlines of a creature as thick as a wagon wheel and three times its length, sighted at dawn where the river narrowed below Lookout Mountain’s looming ridge. Their leather-bound journals described a tail fin resembling a fan carved from driftwood and eyes reflecting the morning sun like burning embers. When they tried to trap or harpoon one, the beast seemed to vanish into the instantaneous churn of the river-bed, leaving limp nets tangled in scale-like debris.

Archaeological digs at old water mills and abandoned distilleries have unearthed bones that defy classification. Vertebrae fragments twice the size of any fish discovered in those streams, along with teeth shaped more like serrated stones than shark fangs. Folklorists theorize these remains belonged to a species perhaps millennia old, driven by shifting currents and glacial melt, seeking refuge in rich sandbars and deep holes carved by ancient floods. Oral histories among Creek and Cherokee tribes speak of water spirits named Uktena or Kanati, guardians of fresh water and bounty, yet vengeful when humans overstepped sacred boundaries. They told of serpents that could shift form, appearing as submerged logs to unsuspecting travelers before unveiling scales brighter than gold dust.

Over time, settlers absorbed and recast these strands into local tapestry. Tavern songs praised the serpents as both omen and deity—adequate tribute for hard labor and poor harvests. Southern preachers, wary of blending pagan lore with Christian doctrine, labeled whispers of serpent gods as heresy, yet even their midnight burnings of grimoire pages left ash flecked with glittering residue. When highway crews later blasted through rock outcrops to lay asphalt, engineers reported equipment destroyed by sudden, inexplicable tremors. The only sign of resistance left behind were gouged imprints in concrete—long, curved indentations too uniform to be random. Each scar, they said, felt like the underwater breath of something alive and unearthly.

Unconfirmed meteorological journals from the late nineteenth century logged sudden shifts in river levels too rapid for seasonal rains. Boats anchored at Muscle Shoals would list unexpectedly, sometimes capsizing without warning, dashing deckhands against submerged snags. Such catastrophes were dismissed as freak currents until survivors spoke of something grazing the hull before the wave—something immense and deliberate. Eyewitnesses claimed they saw arched forms slicing through foam before slipping back into the river’s embrace, leaving wake patterns resembling calligraphy across the water’s surface.

Modern-day scientists, buoyed by remote sonar sweeps and drone reconnaissance, have intensified searches in areas marked by clustered disappearances. Yet sonar waves reflect a labyrinth of hollows and drop-offs, producing echoes indistinguishable from large bodies moving just below silted layers. River sediment has preserved traces of massive undulations but sealed them in opaque stratums often misread as geological anomalies. Every net draw, every underwater light probe, seems to invite the serpents to recede deeper, nurturing the enigma. They remain just beyond detection, reminding observers that there’s a vast, undomesticated world beneath the gentle curves of these southern rivers.

2. Tragedies Along the Currents

By the early twentieth century, headlines sporadically documented river tragedies too peculiar to assign solely to storms or human error. In 1907, the steamboat Magnolia collided with an unseen obstruction near the confluence of the Black Warrior and Tennessee rivers. The hull cracked, and 23 passengers plunged into murky water. Some were found downstream, grievously injured but alive, clinging to mangled lifeboats; others vanished without trace. Onboard musicians later recounted hearing distant chords of a fiddle from the water at dawn—an ethereal melody that faltered beneath churning waves. Their descriptions fueled rumors that the serpents lured victims with hypnotic songs before dragging them into submerged caves.

In 1932, a local fishing captain named Amos Caldwell reported a catastrophe near the Wheeler Dam site. Caldwell’s vessel rode a calm pool when a colossal shadow passed silently beneath, displacing millions of gallons in a single surge. Ropes snapped like twigs, and Caldwell lost both hands to crushing force before bailing himself out with adrenaline-fueled resilience. He survived, yet his fragmented testimony was met with skepticism when he described frilled scales the color of wet slate and a dorsal ridge undulating like a row of spearheads. Physicians noted his strange fever lasting weeks, claiming he’d suffered deep tissue crush wounds allegedly delivered by something armored beyond human craft.

As dams and levees reshaped the rivers during the New Deal era, construction crews logged injuries far exceeding typical accidents. Men spoke of heavy equipment gouged by unseen claws, boats shattered by thunderous booms from below, and sudden whirlpools appearing in placid stretches. One tragic 1941 journal entry detailed fifteen workers lost in a flash flood that bore uncanny signatures—no storm had been forecast, and heavier rains lay downstream. Eyewitnesses insisted they saw a massive neck arch from the murk before the water rose in spiraling columns.

In recent decades, recreational kayakers and explorers have vanished, their GoPro footage recovered showing only swirl patterns and fleeting reflections that suggest a colossal body just beyond frame. Amateur podcasts have inscribed these anomalies into viral lore, tempting thrill-seekers to test the serpents’ domain at sunrise or midnight. Yet rescue divers report impenetrable darkness below fifteen feet, despite powerful submersible lights. They recount an almost tactile sense of presence, like a heavy exhale pressing against wetsuits, and sonar contacts that vanish when approached.

Each tragedy renews the cycle of cautionary tales. Local shrines dot riversides: rusted toy boats for lost children, tarnished pocket watches for anglers swallowed by the current, shards of shattered nets for those who tried to capture the impossible. Villagers pray to unnamed river guardians, leaving offerings of cornmeal and whiskey, hoping to placate old spirits. Even skeptics pause when lanterns sway on foggy mornings, and when unexplained footprints appear at water’s edge—collections of oval imprints too large for deer and too symmetrical for hogs. The tragedies continue to fuel devotion to these age-old legends, embedding the serpents more deeply into the cultural fabric of the South.

3. Encounters and Modern Investigations

In the digital age, scientific curiosity collides with folklore more directly than ever. Biologists deploying remote-operated vehicles in deep river trenches discover odd thermal readings—localized heat pockets implying biological activity far larger than any known fish species. Government researchers have installed underwater acoustic arrays, hoping to record low-frequency calls or mechanical ripples in sonar maps. At the University of Alabama’s aquatic biology department, doctoral candidate Serena Cho logs anomalies daily. She notes rhythmic pulses that don’t correlate with shipping traffic or known wildlife behavior. Spectrographic analyses filter out human noise, leaving what she calls “subsonic song patterns” resonant at intervals of roughly forty seconds—too deliberate for geological turbulence.

Citizen scientists have turned night-vision cameras on levee walls and boat hulls, capturing strange reflections of elongated bodies weaving through water hyacinths. One viral clip shows a translucent outline drifting near a pontoon deck before an abrupt flash of movement—enough to erode public dismissal. Insurance claims for damaged watercraft surge after each viral release, prompting private firms to hire investigative teams. They chart GPS tracks of GPS sails and sonar beacons, but each expedition seems to coincide with a lull in serpent activity. It’s as though the creatures learn from intrusion and choose to vanish until the next lull in scrutiny.

Conspiracy theorists propose that during the Cold War, government agencies attempted to weaponize the river giants as living torpedoes—citing declassified files indicating covert sonar tests. Although no direct evidence supports such claims, ruined warehouses along Muskogee Creek occasionally yield fragments of steel mesh nets stronger than any commercial alloy. Amateur divers speak of discovering prototype enclosures rusted in mud, hinting at ambitious but abandoned experiments. Such speculation blurs the line between government cover-ups and genuine natural wonder, keeping media cycles ablaze.

Meanwhile, eco-activists warn against deep dredging and dam expansions that could drive these ancient beings into extinction, or worse, force them to seek refuge in narrower, more turbulent channels—potentially endangering human communities. Public forums in Florence and Knoxville brim with heated debates over balancing flood control, commercial barge routes, and preservation of unknown species. Some locals have even begun underwater sanctuaries—conservation zones free from chatter of propellers, hoping that silence may coax a final glimpse of the serpents in their unspoiled element.

The true nature of the Tennessee and Alabama river serpents remains wrapped in half-glimpses and aged confessions. Each sonar blip, each ripple spreading from nowhere, reminds us that the world beneath our skiffs holds mysteries older than any road map. Legend and science stride side by side, driven by human fascination with that which refuses to be fully known. And so the serpents continue their silent pilgrimage through deep channels, ghosting beneath currents that carve our history, beckoning both wonder and caution from those who dare to trace their ancient wakes.

Conclusion

Despite centuries of conjecture and tragedy, the serpents of the Tennessee and Alabama rivers endure as potent symbols of nature’s untamable depth. They represent a boundary where human ambition clashes with ancient wisdom, where sonar pings and modern probes can only glimpse outlines before shadows descend again. Their elusiveness illustrates that some mysteries belong to the water itself—an elemental memory preserved in currents and temperature gradients beyond straightforward analysis.

Around Riverside cafés and boat tours, guides still warn novices against venturing too close to known serpent passages. Fishermen leave salted charms on oar handles, superstitious nods to local lore born of hard-earned wariness. Environmentalists and historians collaborate to advocate protective measures—both for river health and for the possibility of undiscovered species. Their efforts thread respect for ancestral knowledge with the rigor of contemporary research.

Ultimately, the true measure of these colossal creatures may not lie in scientific proof or eye-witness footage. It may rest instead in the collective imagination of communities bound by water and legend, in the stories parents pass to children about unseen guardians gliding beneath daily routines. Whether the serpents are flesh and scale or a manifestation of Southern myth, they shape regional identity as indelibly as the rivers that cradle them. With every sunrise that dances across the water’s surface, their silent forms persist—eternal whispers carried downstream, inviting us to remember that beneath placid exteriors, immense and mysterious worlds still wait to be discovered beneath the waves of time and tide.

As long as currents flow and hearts remain curious, the serpents will slither on—symbols of all that we cannot fully fathom but cannot bear to let slip into oblivion either. In that enduring tension between fear and fascination, the legend lives on, as deep and vital as the rivers themselves.