Introduction

Under the waves of brilliant sunlight filtering through dense ceibo branches, the small village of San Bernardino thrummed with quiet magic. Bright red ceibo blossoms drifted across sinewy vines, and the soft hum of cicadas wove alongside the whisper of gentle breezes. At the edge of a thatched cottage lived an elderly weaver named Amalia, whose hands carried the memory of every thread ever spun. Each morning, Amalia knelt beneath a towering ceibo tree to pray and draw inspiration from nature’s quiet designs. On one fateful dawn, she discovered a spider’s web—a shimmering mandala dipped in dew, glistening like a thousand diamonds above the cracked earthen floor. Spellbound, she watched how each filament intersected with flawless precision, how light and shadow danced along its curves. In that moment, a soft melody rose in her heart—a song of creation, echoing the divine harmony weaving through all things. Carrying her needles and threads, Amalia traced the web’s pattern, and slowly, on cotton so white it seemed spun from sunlight, a new lace was born. Word of her creation drifted across the hills and rivers, drawing neighbors and strangers alike to learn from her gentle wisdom. By stitching the spider’s song into cloth, the villagers found not only beauty but purpose, weaving community and identity into every delicate loop of Ñandutí lace.

I. The Spider’s Gift

When Amalia first saw the spider suspended between two low branches of the ceibo, she felt an uncanny kinship with the tiny architect. Its body was slender, its eight legs arranged like the spokes of a living wheel. She knew spiders from watching the granary behind her home, where they ruled over grain and insects alike, but this one seemed almost otherworldly. For days, she returned to the same spot as dawn broke, her breath quiet, her heart calm. In the hush of sunrise, the web unfurled like a woven prayer. Amalia knelt close enough to study its pattern: a central spiral anchored by radial threads, all glinting with silver dew. In careful strokes, she traced lines in the soft earth, replicating every arc and angle. With trembling fingers, she pulled a skein of cotton from her basket and worked the stitches one by one, feeling as though she were translating an ancient language. Villagers paused their chores to watch her. They saw her brow knit in concentration, her lips moving in soft syllables—perhaps a prayer, perhaps a lullaby. By the third morning, Amalia had a small square of lace, its design echoing the spider’s web exactly. She held it aloft in the sunrise, the threads quivering with light. Murmurs of awe rippled through the crowd. Woven into that first piece was the spirit of the ceibo, the earth’s patience, and the courage to transform nature’s gift into art that would endure far longer than the spider’s brief life.

II. Stitches of Community

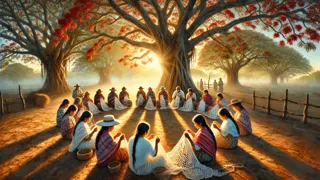

News of Amalia’s lace grew like creeping vines through every settlement on the shores of Lake Ypacaraí. Women from nearby cottages came to learn her technique—young and old, mestiza and Guaraní, all gathered beneath the ceibo’s shade with spools of cotton in hand. Amalia never spoke of secrets; instead, she demonstrated the simplest loop or binding stitch and encouraged her pupils to study the living web. As sunlight filtered through leaves, dozens of hands worked in unison, stitching and knotting patterns that mirrored each other but carried their maker’s pulse. With every stitch, the community found purpose. Children wove tiny ornaments to sell in the local mercados; mothers embroidered shawls that softened the night chill; elders stitched prayerful motifs into altar cloths. The threads bound lives as surely as they bound cloth. Under Amalia’s gentle guidance, the practice became known as Ñandutí—“spider’s web” in Guaraní—honoring the humble architect that inspired them. A new hum rose across fields and plazas, not of cicadas but of women singing as they crocheted: a soft cadenced prayer for rain, for health, for safety. Each night they laid their finished lace on a communal loom so that the next dawn would reveal a tapestry of countless webs, each reflecting dreams and hopes. The first grand piece measured nearly two meters across, its fine threads shining like morning dew; it became the centerpiece of the village’s festival of ceibo, drawing travelers from Asunción and beyond. Merchants marveled at its craftsmanship, and soon orders multiplied. Through each sale, the women lifted their families from hard seasons of drought and flood. Money flowed back into homes, new seeds were planted, and the life of the ceibo grove seemed richer. In sharing their skill, the villagers found that art was more than beauty—it was resilience and unity woven into every knot.

III. Legacy of the Web

Generations passed, but the song of the Ñandutí spider never faded. Long after Amalia’s hands rested from the hymns of cotton and needle, her legacy blossomed across Paraguay and beyond. In bustling towns, apprentices studied her patterns and adapted them into modern furnishings: lampshades that cast floral shadows, table runners that blossomed with color, and bridal veils that shimmered like moonlit webs. International fairs showcased their work, earning recognition for its unique blend of indigenous Guaraní symbolism and colonial-era lace traditions. Meanwhile, back in San Bernardino, children learned at primary schools where Ñandutí patterns adorned every classroom wall, reminding them of their heritage. Artists painted murals of the great ceibo tree, its branches woven with hundreds of tiny spiders spinning webs like living lace. In song and dance, local troupes told the tale of the old weaver and her spider muse, celebrating how nature’s design could transform sorrow into joy, and poverty into pride. In laboratories, scientists marveled at the spider’s silk, studying its strength to inspire new fibers, while anthropologists traced the craft’s journey as a testament to cultural resilience. Throughout all these innovations, the fundamental truth remained: humble inspiration can yield creations of lasting beauty. Even now, when a fresh breeze rattles a spider’s web in the early light, villagers pause to remember the melody Amalia heard beneath the ceibo: the silent hymn of wisdom spinning through the air, weaving hearts and hands into one story. Ñandutí lives on, a testament that every strand—no matter how small—can become part of something greater, a tapestry of community, creativity, and hope.

Conclusion

Today, under the same skies that once witnessed Amalia’s reverent gaze, the Ñandutí tradition thrives in countless hands and hearts. Tourists and collectors seek the lace as symbols of Paraguayan identity, yet in every spindle and hook remains the quiet voice of a spider spinning her web among the ceibo blossoms. From the hush of dawn to the glow of festival lanterns, each piece carries a song—a reminder that the smallest threads, when woven together, can hold up a culture. Whether crafted by a grandmother under a mango tree or embroidered by a young artisan in a bustling workshop, Ñandutí lace speaks of patience, unity, and the beauty that springs when humans heed nature’s quiet teachings. In every looping thread and airy motif, the spirit of that first web lingers, inviting new dreamers to trace its lines and add their own verse to the eternal Song of the Ñandutí Spider.