{{{_Intro}}}

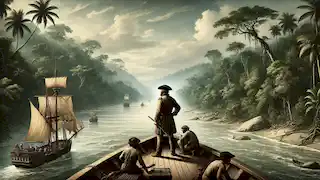

The tale of El Dorado, "The Golden One," has captivated the imaginations of countless adventurers, explorers, and dreamers throughout history. Set in the misty mountains and dense jungles of Colombia, this myth has evolved from a ceremonial ritual of the indigenous Muisca people into a larger-than-life legend of an entire city built of gold. However, beneath the glittering allure of treasure lies a more complex story—one of cultural misunderstanding, conquest, and relentless human ambition. Long before Europeans arrived in South America, the highlands of what is now Colombia were home to the Muisca civilization, a highly organized society that thrived in agriculture, trade, and artistry. The Muisca people occupied a region rich in natural resources, where gold washed down from the mountains and rivers. But unlike the Europeans, the Muisca did not see gold merely as a symbol of wealth or power; for them, it was a sacred material, an offering to the gods. The Muisca territory was divided into two main confederations—the Zipa of Bacatá (modern-day Bogotá) and the Zaque of Hunza (modern-day Tunja). These leaders ruled with a combination of military strength and religious authority, guiding their people through spiritual ceremonies that honored their gods, particularly the sun god, Sué. One of the most important rituals in Muisca culture was the inauguration of a new Zipa, the leader of Bacatá. Upon his ascension to power, a grand ceremony took place at Lake Guatavita, a site considered sacred by the Muisca. This lake, surrounded by steep green hills, was thought to be a gateway to the divine. It was here that the legend of El Dorado was born. The ritual itself was a stunning spectacle of devotion and wealth. The new Zipa would strip down and cover his body in a thick layer of gold dust, transforming himself into a shining, golden figure. He would stand aboard a raft made from reeds, which floated out to the center of the lake. As the raft glided through the misty waters, the Zipa’s attendants would throw gold ornaments, emeralds, and other precious items into the depths as offerings to the gods. At the center of the lake, the Zipa would dive into the water, symbolically washing away the gold and solidifying his role as the chosen one of the gods. This breathtaking display of devotion was never meant to signal wealth or power in the sense understood by the Europeans who would later hear of it. Rather, it was an act of spiritual cleansing and communion with the divine. However, as news of this ritual spread across the Americas and eventually to Europe, the original meaning was lost, replaced by greed-fueled fantasies of an entire city made of gold. The first Europeans to hear the stories of El Dorado were the Spanish conquistadors, who had already struck gold in the conquests of the Aztec and Inca empires. By the early 16th century, tales of vast wealth in the New World had reached fever pitch in Spain. With their victories in Mexico and Peru, the Spanish believed there was no end to the riches South America might hold. So, when rumors of a golden kingdom to the north of the Andes began to circulate, the race to find it began. In 1536, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada set out from Santa Marta on the Caribbean coast with a large expedition of Spanish soldiers, slaves, and indigenous guides. His goal was to push into the interior of Colombia, hoping to locate the source of the gold that had tantalized so many. But the journey was brutal. The dense, uncharted jungle was full of dangers—venomous snakes, disease-carrying insects, torrential rains, and hostile tribes who resisted the Spanish invaders. Food was scarce, and morale plummeted as the men grew sick and weary. Despite the hardships, Quesada was driven by the promise of untold riches. After months of grueling travel, his expedition reached the highlands of the Bogotá savanna, where they encountered the Muisca civilization. While Quesada never found the golden city he sought, he did discover significant amounts of gold in the form of jewelry, ceremonial items, and beautifully crafted artifacts. But this was not enough to satisfy the greed of the conquistadors, whose imaginations had been stoked by the idea of entire cities paved in gold. The Muisca, who had long coexisted peacefully among themselves, were no match for the well-armed Spanish soldiers. Quesada and his men quickly subdued the Muisca rulers and demanded tribute. But even as gold and emeralds flowed into Spanish hands, Quesada remained fixated on the elusive city of El Dorado, convinced that there was more wealth hidden deeper in the mountains. Quesada’s failure to find El Dorado did not dissuade others from trying. His discoveries only served to fuel the legend further, and soon other conquistadors and adventurers embarked on their own quests to find the golden city. Sebastián de Belalcázar, one of the most ruthless and ambitious conquistadors, had already made a name for himself in the conquest of Quito and the founding of cities such as Cali and Popayán. However, hearing of Quesada’s encounters with the Muisca, Belalcázar turned his attention to the legend of El Dorado. Belalcázar’s expedition pushed deep into the northern Andes, hoping to outmaneuver Quesada and claim the golden city for himself. At the same time, German adventurer Nikolaus Federmann, working under the authority of the Welsers, a prominent German banking family, launched his own expedition. Like the Spanish, Federmann was lured by the stories of gold and saw an opportunity to claim a fortune for his German backers. Both Belalcázar and Federmann, along with Quesada, found themselves in a race to find El Dorado, but none of the three achieved their goal. Instead, they met in the Muisca heartland, each attempting to assert their dominance over the territory and its resources. Tensions between the three factions ran high, and disputes over the spoils of conquest nearly erupted into violence. In the end, a tenuous peace was brokered, and the territory was divided, but the legend of El Dorado remained just out of reach. Although these men left Colombia without the treasure they sought, the myth of El Dorado continued to grow. Their failed expeditions became part of the lore, and with each retelling, the city of gold became grander, more elusive, and more desirable. As time passed, the legend of El Dorado expanded beyond the boundaries of Colombia, spreading to other parts of South America. As the Spanish grip on South America tightened, other European powers became increasingly interested in the continent’s wealth. By the late 16th century, England, led by Queen Elizabeth I, sought to undermine Spain’s dominance in the New World. One of the most famous English adventurers of the time, Sir Walter Raleigh, became obsessed with the legend of El Dorado. Raleigh was convinced that the golden city lay somewhere along the Orinoco River in modern-day Venezuela. In 1595, he launched an expedition to find it, determined to bring back treasure to bolster England’s power and prestige. Raleigh’s journey up the Orinoco was fraught with peril. The river snaked through dense, uncharted jungle, and the expedition was plagued by disease, difficult terrain, and hostile indigenous groups. Despite the dangers, Raleigh pressed on, driven by his belief in the existence of the legendary city. His writings from the expedition describe the vast wealth he believed was hidden in the region. He spoke of an "Empire of Guiana," a kingdom rich in gold, waiting to be uncovered. Although Raleigh never found El Dorado, his accounts captured the imagination of many back in England, and his failure did little to quell the enduring belief in the legend. In the centuries that followed, the myth of El Dorado continued to inspire adventurers and treasure hunters. Expeditions were launched well into the 18th century, but none succeeded in finding the elusive city of gold. By this time, the truth behind the legend had become clearer—there was no city of gold, only the spiritual rituals of the Muisca people that had been misinterpreted by European greed. However, the impact of the search for El Dorado was profound. The relentless pursuit of wealth led to the subjugation and exploitation of indigenous populations, the destruction of their cultures, and the reshaping of entire regions. The lust for gold fueled European colonization, leaving scars on the land and its people that would last for generations. In modern Colombia, the story of El Dorado has become part of the country’s cultural heritage. Lake Guatavita remains a symbol of the legend, and many visitors are drawn to its mysterious waters, imagining the rituals that once took place there. In Bogotá, the Gold Museum houses an extraordinary collection of Muisca artifacts, including the famous "Muisca raft," a small golden sculpture that depicts the ceremonial raft used in the Zipa’s inauguration ritual. This golden artifact, discovered in 1969, provides a tangible link to the legend of El Dorado. It serves as a reminder of the true origins of the myth and the spiritual significance of gold to the Muisca people. While the city of gold may never have existed, the artistry and craftsmanship of the Muisca remain as a testament to their culture and history. The story of El Dorado is more than just a tale of treasure hunting—it is a reflection of human ambition, greed, and the destructive consequences of the pursuit of wealth. The conquistadors, driven by their hunger for gold, wrought devastation on the indigenous peoples of the Americas, often without understanding the deeper meanings behind the rituals and cultures they encountered. The legend of El Dorado serves as a cautionary tale, reminding us that the quest for material wealth can lead to the loss of something far more valuable—human life, culture, and dignity. It is a story that echoes through history, warning future generations of the perils of unchecked ambition and the dangers of exploiting others in the pursuit of fortune. Even though the physical city of El Dorado was never found, the myth continues to endure. Today, it remains a symbol of the allure of the unknown and the possibility of discovering something extraordinary. Whether it is depicted in films, literature, or as a part of Colombia’s national identity, the legend of El Dorado has become a timeless story of adventure, mystery, and the eternal human desire for something greater. For those who sought it, El Dorado represented not just wealth, but the ultimate prize—a symbol of triumph over the natural world and the unknown. And for those who continue to be captivated by the story, it remains a reminder that sometimes the greatest treasures are not the ones we find, but the journeys we undertake in search of them.The Kingdom of the Muisca

The Conquistadors and the Quest for El Dorado

The German Expedition and Belalcázar’s Ambition

Sir Walter Raleigh and the Orinoco Expedition

The Legacy of El Dorado

A Cautionary Tale

The Enduring Myth